Emily Carney has written articles for AmericaSpace, Ars Technica, and other online outlets throughout the last decade. She founded the Space Hipsters group on Facebook in 2011, and has her own spaceflight blog called This Space Available

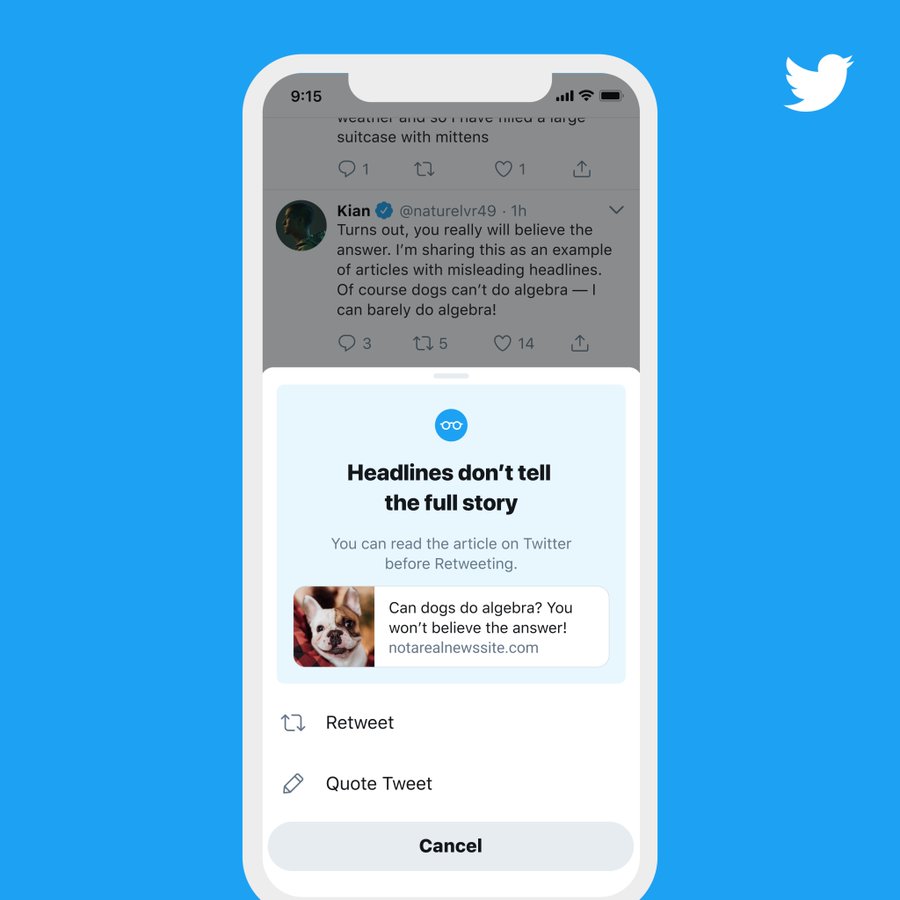

Scientific literacy is key to developing the critical thinking processes that are essential to fueling future discoveries, particularly through the medium of spaceflight.

Since humankind has been able to gaze at the Moon, the Sun, planets, and celestial bodies in the sky, we have been hungry to find out more about what is “out there.” This hunger led to the development of processes to better understand the Universe we live in. This curiosity led to advances in astronomy throughout the centuries before rockets were even developed. Those who didn’t gaze at the skies through sometimes rudimentary telescopes still dreamed about the heavens, illustrating and writing elaborate science fiction stories about space travel. By the early- to mid-Twentieth Century, rocket pioneers used their critical thinking skills to configure increasingly more advanced means of getting armaments into the atmosphere, and eventually into space. They, too, wanted to know what was “out there.”

While the Space Race between the United States and the Soviets was motivated by competition between two Cold War powers, there was also copious interest in sending scientific payloads to space. This non-militaristic interest to find out what lurked in the heavens spurred the creation of entire space agencies, and influenced famous thinkers including James Van Allen, who went on to validate the existence of extensive radiation belts surrounding the Earth. Thinkers like these saw a need, devised increasingly more sophisticated instruments for satellites and payloads, and began making discoveries that would change the way we saw Earth and other worlds.

Again, while the Apollo lunar missions were motivated in part by competition with another world power, thousands of people on the Earth and a select few in space made “exploration at its greatest” possible through the power of critical thinking: could we get a massive rocket into space? What kind of rocket did we need? What kind of rendezvous techniques could be used? What kinds of features were we looking for on the lunar surface? Could we land a space ship on the Moon? By late 1961, two U.S. astronauts had made brief suborbital jaunts barely into space. Scientific literacy took the same country (and humanity) to the Moon less than a decade later, by July 1969.

This spirit didn’t end as the Space Shuttle program came to a close in 2011. The still-aloft International Space Station (ISS) shows that scientific literacy extends from space to the Earth, as astronauts, cosmonauts, and space scientists from different nations work in the areas of materials engineering, space medicine, astronomy, Earth observations, and numerous other disciplines. Each day, we learn more about ourselves through the voluminous observations made in Low Earth Orbit. One day, these missions will be seen as pioneering steps in getting us to deep space destinations, such as Mars or perhaps, again, the Moon.

All of this discovery – some of it by robotic spacecraft, some by human beings – wouldn’t be possible without the questioning processes of critical thinking, which is essential in better developing scientific literacy for all humankind. Scientific literacy made the “discovery learning” that started centuries ago and currently takes place aboard the ISS wholly possible.

Thanks to Emily Carney for the contribution!

If you work in a field of science and wish to make your voice heard please use our contact page!

Also read Statement on Scientific Literacy from a Science Teacher